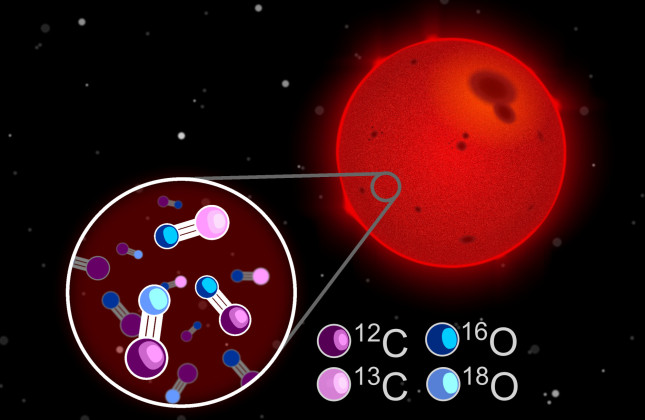

The fundamental question about the origin of carbon and oxygen in our universe has preoccupied astronomers for decades. These elements are not only important ingredients of the human body but are also among the most abundant elements in the universe. But in the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang, these atoms did not yet exist. Almost everything we see around us, is built from atoms that were forged in the hot centres of stars. From the most basic atoms, hydrogen and helium, massive stars produce heavier elements such as carbon, nitrogen and oxygen.

“Nuclear fusion in stars is a complex process and is just the starting point of chemical evolution”, says Darío González Picos (Leiden University), who headed the research. When a star reaches the end of its life, this newly forged material is dispersed out into space, either by gently shedding its outer layers or a dramatic supernova explosion. This cosmic recycling enriches the gas in our Milky Way, providing the raw material from which new stars and planets like Earth will form. Each star’s light therefore carries a chemical fingerprint of this history.

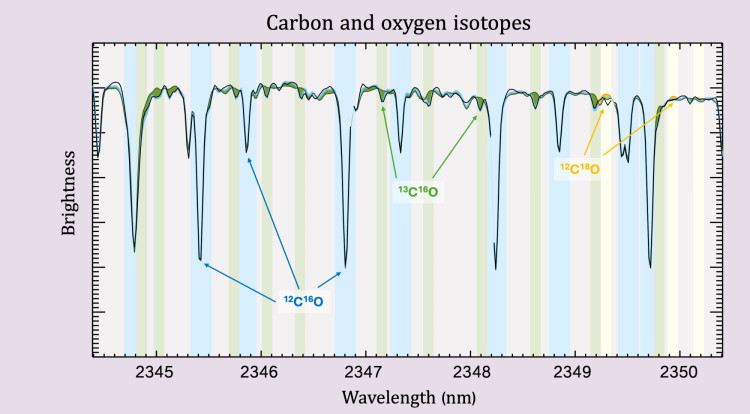

Text continues after figure

A small snippet of the observed spectrum of one of the nearby red dwarf stars. The strong lines of carbon-monoxide are caused by the common isotopes of carbon and oxygen (12C16O - blue). Carbon-13 is typically 100x more rate and forms the much weaker 13C16O lines (green). One can even see a small amount of oxygen-18 that forms 12C18O (in yellow). Credit: Leiden University/Ignas Snellen.

The team of González Picos, Ignas Snellen, and Sam de Regt have found a new way to read these chemical fingerprints by studying isotopes – different varieties of an element. While the number of protons sets the chemical properties of an element (e.g. 6 for carbon), the number of neutrons can vary. On Earth, 99% of carbon atoms have 6 neutrons, but a small fraction has 7. The team has now successfully measured these isotope ratios for both carbon and oxygen in 32 neighbouring stars with unprecedented precision.

“We now see that stars that are less chemically enriched than the Sun have fewer of these minor isotopes”, says co-authorSam de Regt (Leiden University). “This finding confirms what some models of galactic chemical evolution have predicted and now provides a new tool to rewind the chemical clock of the cosmos.”

What is remarkable about this study is that all the data used comes from the archives of a telescope on the island of Hawaii, the Canada France Hawaii Telescope (CHFT). "The observations were originally made for a completely different reason than the one we are using them for now", says co-author Ignas Snellen (Leiden University). "It was entirely Darío's idea to use the high-resolution spectra, which were actually intended for the discovery of planets, for this isotope research – with impressive results."

González Picos concludes: “This cosmic detective story is ultimately about our own origins, helping us to understand our place in the long chain of astrophysical events, and why our world looks the way it does”.