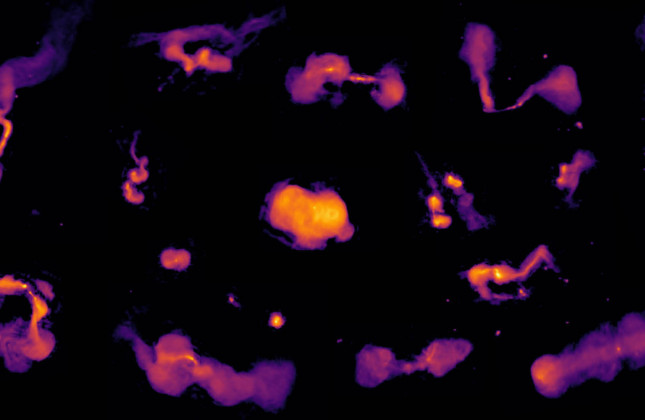

By observing the sky at low radio frequencies, the survey reveals a dramatically different view of the universe than that seen at optical wavelengths. Much of the detected emission arises from relativistic particles moving through magnetic fields, allowing astronomers to trace energetic phenomena such as powerful jets from supermassive black holes and galaxies undergoing extreme star formation across cosmic time.

Thanks to its remarkable detail, the survey has also exposed rare and elusive objects, including merging clusters of galaxies, faint supernova remnants, and flaring or interacting stars. The survey is already enabling hundreds of new studies across astronomy, offering fresh insights into the formation and evolution of cosmic structures, how particles are accelerated to extreme energies, and cosmic magnetic fields, while also making publicly available the most sensitive wide-area radio maps of the universe ever produced.

A decade of international collaboration

"This data release brings together more than a decade of observations, large-scale data processing and scientific analysis by an international research team,” says Dr. Timothy Shimwell, lead author and astronomer at ASTRON and Leiden University, Netherlands.

The achievement showcases the LOFAR European Research Infrastructure Consortium (LOFAR ERIC) model, bringing together expertise from the Netherlands, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Poland, Italy, Sweden, Ireland, Latvia, and Bulgaria. LOFAR's unique design incorporates 38 stations in the Netherlands, and 14 international stations across Europe, with the most distant stations separated by nearly 2,000 kilometres, forming one of the world’s largest, highest-resolution and most sensitive radio telescopes.

Transformative discoveries

While the scientific exploitation is only just beginning, the scale, sensitivity and resolution of the survey are already transforming radio astronomy, enabling new discoveries across a wide range of cosmic environments.

"We can study a diverse population of supermassive black holes and their radio jets at different stages of their evolution, showing how their properties depend not only on the black hole itself, but also on the galaxy and environment in which it resides,” notes Prof. Martin Hardcastle of the University of Hertfordshire, UK. At the same time, the survey has delivered robust measurements of star formation rates in millions of galaxies, showing how these rates vary with galaxy properties and across cosmic time.

“By studying many galaxy clusters, we can show that giant shocks and turbulence drive particle acceleration and strengthen magnetic fields across millions of light-years, something we now see to be happening far more than previously anticipated,” adds Dr. Andrea Botteon of INAF in Bologna, Italy.

The data are being carefully searched for rare astrophysical phenomena, and the team have already uncovered several, including transient and variable radio sources, previously unknown supernova remnants, some of the largest and oldest known radio galaxies, and radio emission consistent with interactions between exoplanets and their host stars.

Technical innovation

Processing the data required the development of new techniques that accurately correct for severe distortions caused by the Earth’s ionosphere, the electrically charged layer of the upper atmosphere. To make the processing of 13,000 hours of observations feasible, these advances had to be combined with robust automation and optimisation.

“The software challenge was enormous,” says Dr. Cyril Tasse of the Paris Observatory, France, who led algorithm development. “It took years to design, refine and optimise the algorithms, but they now allow us to routinely produce extremely sharp and detailed images of the low-frequency radio sky, and hunt for time-variable signals from stars and exoplanets.”

Extracting the data from the telescope archives and distributing the computational workload across multiple high-performance computing systems posed an additional challenge. “The volume of data we handled - 18.6 petabytes in total - was immense and required continuous processing and monitoring over many years, using more than 20 million core hours of computing time,” says Dr. Alexander Drabent of Thuringian State Observatory, Germany.

Looking forward

With LOFAR currently undergoing an upgrade to LOFAR2.0, the collaboration plans to build upon LoTSS-DR3 and utilise the two-fold increase in survey speed offered by the upgraded instrument. Recent advances in data processing are also making it increasingly feasible to image the survey data at much higher resolution, opening the door to even more detailed studies.

“LoTSS-DR3 is not an endpoint, but a major milestone”, notes Square Kilometer Array Observatory scientist Dr. Wendy Williams. “New facilities such as LOFAR2.0 will allow us to map the radio universe with even greater sensitivity and resolution, extending the legacy of this survey well into the future.”