It has long been known that supermassive black holes are messy eaters, but capturing their exact eating habits has proven difficult. Until now.

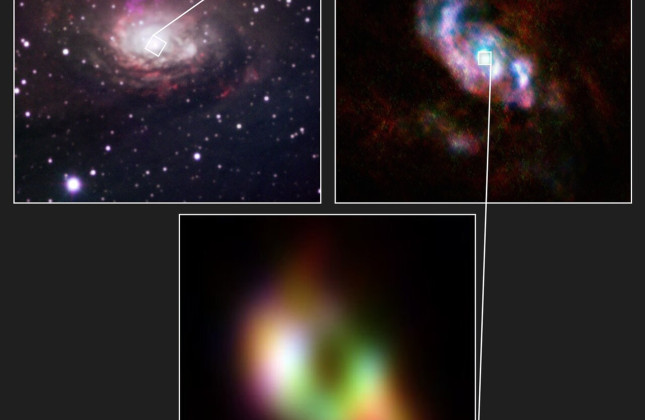

Wout Goesaert, who is now a PhD student at Leiden University, studied ALMA observations of the Circinus Galaxy in 2023 while he was a master's student in Leiden. This galaxy is located in the southern constellation of Circinus (latin for a pair of compasses), just 13 million light-years from Earth. Although it is one of the closest large galaxies, it was only discovered in 1977 because it is hidden behind the disk of the Milky Way.

The observations made by the ALMA observatory, when combined with models, suggest the presence of two spiral arms around the central supermassive black hole. Goesaert and colleagues demonstrated that gas flows through these spiral arms toward the black hole.

"In cartoons, you sometimes see a disc of gas disappearing into a black hole as if it were a whirlpool. However, if there is no supply channel, such a disc will continue to spin around at a decent distance forever," explains Goesaert. "So you need a passageway of some kind. And that’s where our spiral arms come into play."

"As Wout started his research in our team, another group published a paper on the same data and the same black hole. That worried us," says Violette Impellizzeri, Wout's master thesis supervisor at ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy. "However, we decided not to give up and delved deeper into the subject, searching for more details."

Thanks to additional ALMA data and more sophisticated modelling than their competitors, the researchers discovered the two spiral arms. They calculated that the gas in the arms is moving inwards at speeds of up to 150,000 km per hour. Furthermore, it seems that only at most 12% of the incoming matter actually disappears into the black hole. The rest is ejected again before reaching the black hole.

The initial results are begging for more. Why does so little matter reach the black hole? Do all supermassive black holes have spiral arms like this? Does the ejected matter eventually fall back into the black hole like a fountain in a pond, or does it end up further away and trigger star formation? The researchers hope to find the answers using the Event Horizon Telescope, which took the iconic first photos of supermassive black holes, and the ELT, which is under construction in Chile.

Scientific paper

The image is ESO's Photo of the Week